|

| Because for fucks sake, these are not equally-valid sources!!! |

Your Drunk Uncle at Thanksgiving: "We're pumping poor babies full of mercury before they're even 6 months old!"

|

| Your Drunk Uncle (Sam) |

YDUaT: "Yeah, well vaccines also cause autism! That playboy bunny says so."

You: "The one article that ever showed a link was debunked; that guy was 100% lying. Also please take health advice from your doctor, not a celebrity."

YDUaT: "We don't bother to test whether giving vaccines to babies so fast is a bad thing or not! Nobody looks at this stuff. Poor babies."

You: "Scientists totally test that shit. Also, would you rather your kids got measles and died? You make no sense to me."

Seems pretty self-explanatory: someone tells you about a bullshit theory and you tell them how they're wrong, their minds heal and become better and everyone is happy, right? Yeah, we wish. Unfortunately for you and our country, the mind is a tricksy place. Ask your uncle after your conversation about some vaccination myths, and he'll likely get about 20% of those myths wrong still. Ask him 3 days later he will still retain on average, a belief in about 40% of the myths that he previously asserted. What's even worse is that since he has talked to you, his well-educated niece or nephew about it, he now has a reinforcing valid "source" - you. Oops!

It turns out that addressing the illogical with the logical is actually not that effective for eliminating myths and misconceptions. In fact, if you try and debunk a myth you can often end up reinforcing it instead simply by talking about it. So what's the best way to convince the Drunk Uncles of the world to join the 21st century, regardless of the topic? Here we lay out the commandments of Myth Debunking, the cardinal rules of how to work around people's crazy to get them to hear the logic of your actual content. These rules are our own, but we've compiled them after reading up on the psychology of bias emergence and attenuation. That's right. We read psychology papers for you mother fuckers, because we love our country. 'MERICA.

|

| 'MERICA. Sidenote: if you've never googled "the most patriotic picture ever" then you need to. This picture nearly lost to the Star Spangled Donuts that were further down the page. |

The 5 Commandments of Myth Debunking

1) Social consensus hasn't got your back

|

| "Everyone else is doing it" = good enough |

In politics and science, this means that instead of doing research, plenty of people (or sheeple, perhaps) will simply go with what they think is the flow. The way they find the flow is by hearing the same things over, and over, and over again: repetition, even of a lie, is an effective way to convince people that something batshit-crazy is a commonly upheld belief (and therefore, likely to be true). Basically, if your friends think it is true it probably is true... because thinking critically about every dumb thing your friends or neighbors or well-meaning strangers say is absolutely exhausting and you have laundry to do.

Incidentally, this is why it is such a goddamned shame that news institutions insist on giving equal weight to both sides of each story. Scientific consensus might dictate that 98% of the time spent talking about climate change should be "oh shit it is happening" and 2% be "are we sure?" but journalistic integrity takes that and makes it 50-50... which just reinforces the myths instead of the truth. The more that someone hears a myth, the more likely they are to give it some validity - which is why, above all else, you must avoid inadvertently reinforcing your myth.

2) Highlight your answer, not the myth

It seems like circular logic but if you want to debunk a myth, you have to NOT TALK ABOUT IT. And please, for fuck's sake... don't bold it. Take for example, this really great article on GMOs by Pop Sci. That article follows the pretty standard (and logical) debunking formula: it bolds the myth so people know what they're fighting, then provides evidence that refutes it. Here's an example from the article:A person who loves eating Grapples is going to come out of that article with serious pro-Grapple ammunition. A person who thinks GMOs are essentially vegetative cancer sees a bold sentence exactly reinforcing what they thought was true (or even worse, a myth they hadn't heard about yet), some smaller sentences that they kind of forget, and they leave that article with little to nothing resolved. By highlighting the very myths that PopSci has hoped to combat, they have inadvertently reinforced that myth.

But this argument could easily be phrased in a way that avoids reinforcing the myth while still getting the point across. For example, if you're trying to refute the idea that all researchers are in the pocket of the government, try offering alternative reasons for why that wouldn't be.:

Or:

By avoiding repeating the myth itself, and providing evidence that isn't directly linked to the original concept, you have effectively provided an alternate source of information without incidental reinforcement. No longer are researchers solely in the pockets of a seedy underbelly of Big Ag (haha get it??), but actively trying to make a name for themselves by flaying Big Ag out for the world to see. You haven't directly linked "sexy science" with "not funded by big Ag" but have provided an alternate way of looking at the issue: dispelling, without reinforcing.

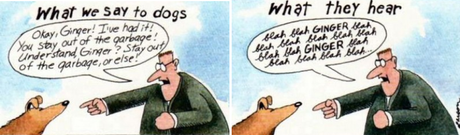

3) People forget the "don't" and just remember the noun.

Avoiding the original myth is especially important because it forces you to navigate around the pitfalls of the "Negation Tag." Research by Ruth Mayo, a researcher at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, found that the critical "nope totally doesn't" tag tends to disappear over time because it's an extra element to a sentence that can make it harder to remember. If instead of saying "no that doesn't cause cancer" you can say "that is completely harmless" you can avoid the problems of your audience remembering 50% of your conversation. |

| Like this, but way worse. |

4) But be careful to not avoid that shit

|

| Exhibit A: The more nobody wanted to talk about Benghazi... the more that she did. |

5) Information overload = only good if they can find it.

Having extra alternatives and answers is only a boon when they come easily to mind or to google searching. Essentially if people don't know the answer or can't quickly find the answer, they assume that the original assertion is correct. If something is only on the back 20 pages of Google then it loses credibility: it's not easily accessible and therefore must not be correct. This works for |

| Might we suggest the fantastic Teach the Consensus T-shirt that this headless Snoop Doggleganger is wearing? |

What's the best way to combat this, other than to really know your shit? Create webpages, google bomb them, and constantly talk about it. Have check-lists of conversational topics if you know you're going to fight the good fight at Thanksgiving. That and maybe wear political T-shirts or something. Yes, filling your facebook with that shit seems repetitive... but that's kind of the point. If they can find it easily, you can overcome the dumber side of social consensus.

6) If They Think There's Harm, Don't Deny It Completely

People are fucking paranoid. They think others are lying to them, even more so when it completely contradicts what they already know. You know that it's true - that's why smartphones come out so often during drunken bar arguments, because you think someone is lying to you or completely missing the point.

|

| "I only hit her for a little bit during that photo session!" is better than "No I totally didn't beat her up with a cow femur!" |

Research has shown that people are more inclined to listen to an argument that states vaccinations have weak risk than they were to arguments that state there is none (Betsch and Sasche 2013). This can be tricky to navigate as you must somehow admit that there are weaknesses to your argument without falling prey to the "don't reinforce the myth" commandment. I.E. "GMOs are healthy, but Monsanto is maybe still a giant bag of copywriting dicks."

7) Find A Way To Make Your Message Resonate

If you can frame your message in the context of your audience, it makes it feel more persuasive. Uskul and Oyserman (2010) found that participants experienced different levels of belief in the need to quit caffeine if they framed it according to cultural context. European American coffee drinkers were more likely to consider quitting if it was framed as some sort of self-improvement; Asian Americans were more likely to quit if it was for a broader sense of good. So if you're talking about climate change with someone, ask if they own beach-front property, or have relatives in New Orleans. If you're discussing the finer points of GMOs, talk about how increased modification can minimize need to chop down forests for farmland, and also feed the poor. Or if you're talking to an asshole, just point out that GMOs are frequently cheaper and require less pesticide use.

If you can frame your message in the context of your audience, it makes it feel more persuasive. Uskul and Oyserman (2010) found that participants experienced different levels of belief in the need to quit caffeine if they framed it according to cultural context. European American coffee drinkers were more likely to consider quitting if it was framed as some sort of self-improvement; Asian Americans were more likely to quit if it was for a broader sense of good. So if you're talking about climate change with someone, ask if they own beach-front property, or have relatives in New Orleans. If you're discussing the finer points of GMOs, talk about how increased modification can minimize need to chop down forests for farmland, and also feed the poor. Or if you're talking to an asshole, just point out that GMOs are frequently cheaper and require less pesticide use.8) Your source isn't as credible as you hopefully are

A study conducted by Cho, Martens, Kim, and Rodriguez (2011) showed were equally as likely to believe messages denying climate change that were listed as "funded by Exxon" or "funded from donations by people like you," simply because of the persuasiveness of the message. As scientists, that can sometimes be hard to believe because we spend so much time verifying sources and looking for biases.

For fuck's sake - even just hearing a name of a source more than once makes it seem more familiar and therefore more likely to be credible (Jacoby, Kelley, Brown, & Jaseschko, 1989).

|

| By the third time, this guy's basically spouting primary literature. |

So while we often focus on talking about how not credible certain myth-sprouting sources are, it might be better to focus on the topic at hand. Yes, the guy who linked autism and vaccines was lying... but more importantly, what about the thousands of articles since then that have show genetic links for autism and no relationship to vaccines? Also remember that you, yourself, are a source: be as credible and believable and rational as you can, and hope that's enough to contradict the Glenn Becks of the world.

9) Um, also guess what if you're foreign, people are less likely to believe you.

Yeah, that's right - just one more area where foreigners are treated differently is in the field of myth debunking (even if you are British and sound like Dr. Who, who seems like a pretty reputable and well-informed gentleman). Oddly it appears to be because they can't understand you as easily, not because they're racist. So that's... good, we guess.In summary:

Don't repeat the myth, but don't be quiet about it either. Say the fact over and over again: open those damn floodgates and spew knowledge in as many different ways with as many different pieces of evidence as you can quickly muster - but don't think that whipping out reason #46 30 minutes after desert has settled and the turkey's gone cold is going to win you any points. Simultaneously, don't deny the downfalls of whatever topic you are discussing: yes, we don't know exactly how much the Earth is going to heat up and no, mercury in large doses isn't nutritious or delicious. Make your truth as relatable as it can possibly be: tailor your message to your audience. Nobody cares if you're citing wikipedia as long as you sound like you know what you're talking about. And finally.... try to speak 'Merican. We don't understand anything else really. |

| Good luck out there, and always remember: if you sound confident you can be an expert even in the weirdest of scenarios. |

REFERENCES

Betsch, Cornelia, and Katharina Sachse. "Debunking vaccination myths: Strong risk negations can increase perceived vaccination risks." Health psychology32.2 (2013): 146.

Cho, C. H., Martens, M. L., Kim, H., & Rodrigue, M. (2011). Astroturfing global warming: It isn’t always greener on the other side of the fence. Journal of Business Ethics, 104, 571–587.

Ding, Ding, et al. "Support for climate policy and societal action are linked to perceptions about scientific agreement." Nature Climate Change 1.9 (2011): 462-466.

Ferrin, Donald L., et al. "Silence speaks volumes: the effectiveness of reticence in comparison to apology and denial for responding to integrity-and competence-based trust violations." Journal of Applied Psychology 92.4 (2007): 893.

Jacoby, L. L., Kelley, C. M., Brown, J., & Jaseschko, J. (1989). Becoming famous overnight: Limits on the ability to avoid unconscious influences of the past. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 326–338

Lev-Ari, Shiri, and Boaz Keysar. "Why don't we believe non-native speakers? The influence of accent on credibility." Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 46.6 (2010): 1093-1096.

Lewandowsky, Stephan, et al. "Misinformation and its correction continued influence and successful debiasing." Psychological Science in the Public Interest 13.3 (2012): 106-131.

Maibach, Edward W., Connie Roser-Renouf, and Anthony Leiserowitz. "Communication and marketing as climate change–intervention assets: A public health perspective." American journal of preventive medicine 35.5 (2008): 488-500.

Mayo, Ruth, Yaacov Schul, and Eugene Burnstein. "“I am not guilty” vs “I am innocent”: successful negation may depend on the schema used for its encoding." Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 40.4 (2004): 433-449.

Nyhan, Brendan. "Why the" Death Panel" Myth Wouldn't Die: Misinformation in the Health Care Reform Debate." The Forum. Vol. 8. No. 1. 2010.

Schwarz, Norbert, et al. "Metacognitive experiences and the intricacies of setting people straight: Implications for debiasing and public information campaigns." Advances in experimental social psychology 39 (2007): 127.

Whittlesea, B. W. A., Jacoby, L. L., & Girard, K. (1990). Illusions of immediate memory: Evidence of an attributional basis for feelings of familiarity and perceptual quality. Journal of Memory and Language, 29, 716–732.

http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/SafetyAvailability/VaccineSafety/UCM096228

http://freedom-school.com/reading-room/persistence-of-myths-could-alter-public-policy-approach.pdf

No comments:

Post a Comment